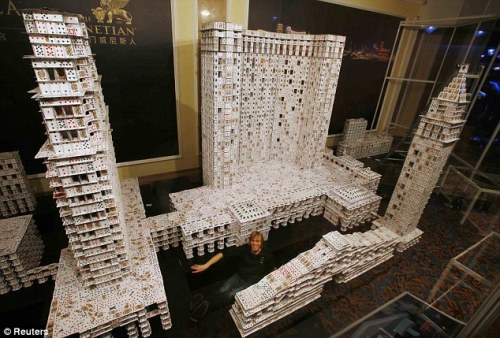

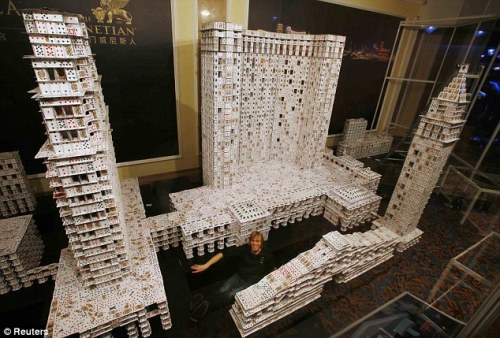

This architect had 44 days of free time to use 218,792 cards to build a giant house of cards.

Link

Via The Daily What

He still has to line up financing, he said, but that isn’t his biggest hurdle.

“It’s the city,” he said.

The issue is over zoning. He and a proponent of the project, City Councilman Tom Gallagher, say the property at 1209 S. Nevada Ave. is already permitted for use as a campground. But Koscielski said city planners are treating it as a new development that would place cumbersome stipulations on the project.

6. I have means by secret and tortuous mines and ways, made without noise, to reach a designated spot, even if it were needed to pass under a trench or a river.

7. I will make covered chariots, safe and unattackable, which, entering among the enemy with their artillery, there is no body of men so great but they would break them. And behind these, infantry could follow quite unhurt and without any hindrance.

8. In case of need I will make big guns, mortars, and light ordnance of fine and useful forms, out of the common type.

Olmsted designed Vandergrift, 35 miles northeast of Pittsburgh, with no right angles, instead following the curves of the river. He also used curving paths to blur movement among pedestrians and hedges to buffer commercialism. Street corners and the buildings on them were rounded. Parks dotted the hilly landscape, and the town was walkable.

When the Illinois study looked at cases where engineers had taken the time to labor over sophisticated energy models, it found that 75 percent of those buildings fell short of expectations. The fault presumably lay with building managers who made numerous small mistakes—overheating, overcooling, misusing timers, miscalibrating equipment.

While some true believers hope PRT will eventually become a dominant mode of transit, others see it more as a gap-filler. It could serve places like airports, university campuses, and medical centers. As a “distributor,” it could branch out into less dense areas to bring riders to other mass transit hubs. And it could provide a valuable service in “edge cities,” to ferry people from residential areas to shopping areas or office parks - routes that are now taken almost exclusively in automobiles.

There's a certain attractiveness to New Orleans, Mexico City or Naples—where you get the sense that though some order exists, it's an order of a fluid and flexible nature. Sometimes too flexible, but a little bit of that sense of excitement and possibility is something I'd wish for in a city. A little touch of chaos and danger makes a city sexy.

The environmental benefits of checking pro-suburb subsidies are real, but they are smaller than many people think. That's from the National Academy of Sciences and the authors are no haters of the environment. If you check out p.59, you'll see that a forty percent increase in population density decreases vehicle miles traveled by less than five percent.

555 KUBIK_ extended version from urbanscreen on Vimeo.

Bright Tree Village is an exemplar of sustainable, low-tech development. This Ewok settlement on the forest moon of Endor follows the traditional pattern: thatched-roof huts are arranged on the main branches of a tree around the chief’s hut on the trunk. Rated BREEAM Excellent, the development - by architect Wicket W Warrick - makes use of locally sourced materials, is carbon-neutral and far exceeds Endor’s notoriously strict building regulations.

Perhaps the most striking—and uniquely American—aspect of the Plan was its idealistic belief in Chicago as a city without limits. The planners believed their city could become the most beautiful and prosperous in the world, and they inspired its citizens to undertake the challenge.

Some of the runoff gets in an underground cistern. During dry weather, this storage tank provides water to the pond. During heavy rains, excess water flows from the pond into the rain garden, simulating the hydrological dynamics of a floodplain environment. Water seeps through the soil and gets naturally filtered.

The mathematics of cities was launched in 1949 when George Zipf, a linguist working at Harvard, reported a striking regularity in the size distribution of cities. He noticed that if you tabulate the biggest cities in a given country and rank them according to their populations, the largest city is always about twice as big as the second largest, and three times as big as the third largest, and so on. In other words, the population of a city is, to a good approximation, inversely proportional to its rank. Why this should be true, no one knows.

Even more amazingly, Zipf’s law has apparently held for at least 100 years. Given the different social conditions from country to country, the different patterns of migration a century ago and many other variables that you’d think would make a difference, the generality of Zipf’s law is astonishing.

Keep in mind that this pattern emerged on its own. No city planner imposed it, and no citizens conspired to make it happen. Something is enforcing this invisible law, but we’re still in the dark about what that something might be.

This implies that the bigger a city is, the fewer gas stations it has per person. Put simply, bigger cities enjoy economies of scale. In this sense, bigger is greener.

The same pattern holds for other measures of infrastructure. Whether you measure miles of roadway or length of electrical cables, you find that all of these also decrease, per person, as city size increases. And all show an exponent between 0.7 and 0.9.

Now comes the spooky part. The same law is true for living things. That is, if you mentally replace cities by organisms and city size by body weight, the mathematical pattern remains the same.